Born in the French Duchy of Lorraine, Margaret of Anjou grew up in France before her marriage to Henry VI in 1445. The marriage was somewhat controversial, in that there was no dowry given to the English Crown for Margaret by the French. Instead it was agreed that Charles VII of France, who was at war with Henry in The Hundred Years' War in France, would be given the lands of Maine and Anjou from the English. When this decision became public, it tore up already fractured relationships amongst the king’s council.

She was fifteen years old when she was crowned queen consort at Westminster Abbey. She was described as beautiful, and furthermore 'already a woman: passionate and proud and strong-willed'.

A breakdown in law and order, corruption, the distribution of royal land to the king's court favourites, and the continued loss of land in France meant Henry and his French queen’s rule became unpopular. Returning troops, who had often not been paid, added to the lawlessness and prompted a rebellion by Jack Cade.

Henry lost Normandy in 1450 and other French territory followed. Soon only Calais remained. This loss weakened Henry and is thought to have started the breakdown of his mental health.

Margaret gave birth to their only son, Edward of Lancaster, in 1453. It was rumoured that the king was incapable of fathering a child and that the baby was the result of an affair between Margaret and one of her favourites; Edmund Beaufort 1st Duke of Somerset and James Butler Earl of Wiltshire were both named as possible fathers. But there’s no evidence to confirm this and Henry certainly accepted the boy as his own.

Unable to rouse Henry from his catatonic state, Margaret ruled the kingdom in his place. It was she who called for a Great Council in May 1455 that excluded Richard Duke of York, sparking the series of battles between York and Lancaster that would last more than thirty years.

Margaret attempted to raise support for the Lancastrian cause. Lancaster won at the Battle of Wakefield where the Duke of York was beheaded, and followed up with a victory at the Second Battle of St Albans (at which she was present) against Warwick, recapturing her husband. But the Yorks won at Towton in 1461, led by the duke’s son Edward, who deposed King Henry and proclaimed himself Edward IV.

Margaret took her son Edward and fled to Scotland and plotted their return. When Warwick fell out with Edward over his marriage to Elizabeth Woodville, Margaret and he formed an alliance; together they restored Henry to the throne. To cement their deal, Warwick’s daughter, Anne Neville, was married to Margaret's son Edward.

Their success was brief; Margaret was taken prisoner by the victorious Yorkists after the Lancastrian defeat at Tewkesbury, where her son Edward was killed. In 1475, she was ransomed by her cousin, King Louis XI of France. She went to live in France as a poor relation of the French king, and she died there at the age of 52.

Margaret’s energy, ambitions and commitment to her cause is a struggle for some male historians; by some she has been considered to be a pseudo-man. Polydore Vergil described her as ‘A woman of sufficient forecast, very desirous of renown, full of policy, council, comely behaviour, and all manly qualities …’. This is the start of the interrogation of Queen Margaret of Anjou’s femininity that has gone on until our own times. In a very little while this queen who fought so courageously for her son, her husband, and her House, would become not even a man but described by Shakespeare as a beast: a ‘she-wolf'.

She-wolf of France, but worse than wolves of France...

Women are soft, mild, pitiful, and flexible;

Thou stern, obdurate, flinty, rough, remorseless

SOURCE: Shakespeare, W. Henry VI: Part III, 1.4.111, 141-142

‘We are to go to France with a great party to fetch home the king’s bride.’

‘It has been decided?’ The marriage of Henry has been a long time coming. My own first husband, Lord John, was picking out French princesses for him, when I was a new bride. ‘At last?’

‘You have missed all the gossip while you were in confinement, but yes, it is decided at last. And she is a kinswoman to you.’

‘Margaret!’ I guess at once. ‘Margaret of Anjou.’

He kisses me as a reward. ‘Very clever, and since your sister is married to her uncle, you and I are to go and fetch her from France.’

From The White Queen

Behind their train comes Margaret of Anjou seated on a litter drawn by mules, white faced and grim. They don't exactly bind her hands and feet and put a silver chain around her throat, but I think everyone understands well enough that this woman is defeated and will not rise from her defeat. I take Elizabeth with me when I greet Edward at the gate of the Tower because I want my little daughter to see this woman, who has been a terror to her for all her five years, to see her defeated and to know that we are all safe from the woman she calls the Bad Queen.

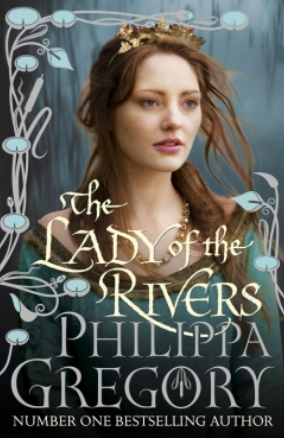

Image: Margaret of Anjou receiving the Book of Romances. From an illuminated manuscript by the Talbot Master (circa 1445, British Library).