8th June 2020

Edward Colston and I go back a long way. I first came across him in 1968 when I won a scholarship funded by him, to attend a school founded by him: Colston’s School for Girls, I learned the school’s tradition of founder's day - when the choir, me among them, sung ‘Let us Praise All Famous Men’, and the entire senior school wore his favourite flower - bronze chrysanthemums - in our buttonholes and threw them at his statue by way of thanks for our education and for the many Bristol facilities that he established - from alms houses, to the famous Colston Hall.

I only learned of his connection with the slave trade in an exceptionional sermon at my last founder's day at school - which let the cat out of the bag before the barely-listening schoolgirls. Though we had by then all studied slavery in our history lessons, no-one had made the controversial connection between our school and slavery. With growing amazement, I learned that Edward Colston was born in Bristol in 1636 to a wealthy merchant family. Leaving for London he was a successful trader, joining the Royal Africa Company where he, working under a Royal warrant, traded more than 85,000 slaves including 12,000 children, of whom more than 19,000 died.

Edward Colston became chief executive - the Deputy Governor - before he retired to Bristol with his massive fortune. He returned to a city which had been the second greatest slaving city in England and he was welcomed as a successful son. His statue was erected a decade AFTER the abolition of slavery, and was intended to honour him, a man who had made his fortune from cruel and inhumane activity, in the very heart of a slave-trading city.

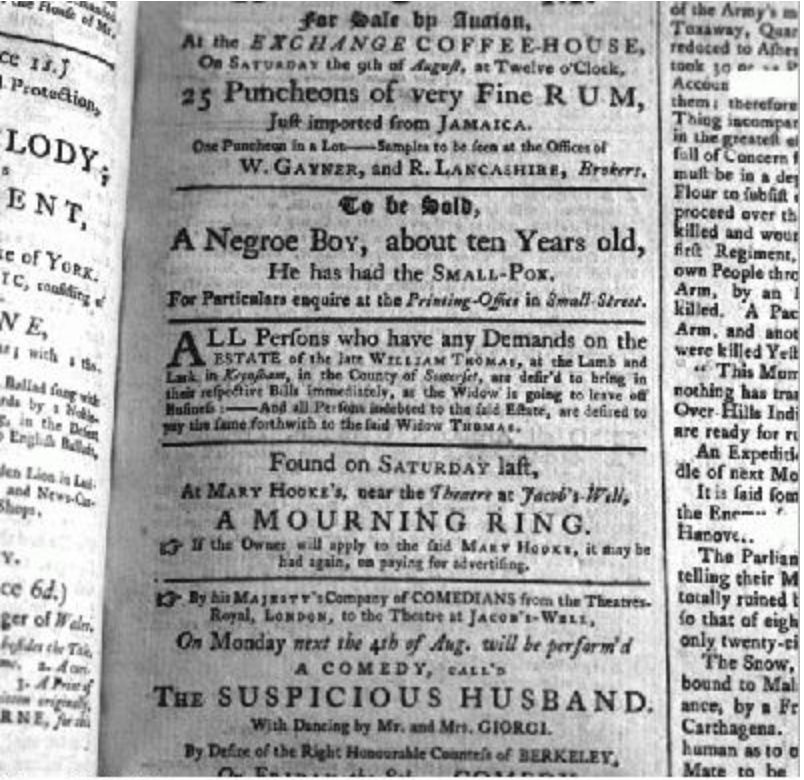

Years later, in 1995, I wrote A Respectable Trade. A novel set in 1787, about the almost-unknown slaves who were trafficked and exploited in England. At the time, though anyone could read the dozens of daily advertisements for runaway slaves in eighteenth century newspapers, there was a lazy assumption by most historians that these were personal slaves brought into England by returning West Indian planters. In fact, African slaves were directly imported into England, mostly for domestic work, black children especially little boys, became a fashion accessory as pageboys. The novel was intended to fictionalise a history which was little known, and still denied. When I adapted it for a BBC TV series there was a renewed interest in Bristol where more and more people were starting to explore the city’s links with slavery.

The people of Bristol have been discussing what to do with Colston’s statue for years. I believe it should have been taken down long ago, carefully and responsibly as a work of art (not very good art) and an important document of history. Maybe after World War II when Bristol was protected by black American soldiers, as a way of thanking them? Maybe after the St Paul’s riot in 1980? Maybe after the petition signed by 11,000 people? In 2018 the council agreed to add a plaque noting his involvement in the slave trade but no-one could agree on the wording - a not untypical problem for a city which has always been reticent about its slaving past.

But now - since the authorities didn’t quite want to bite the bullet - the people have done it for them. Next will come the debate as to what should be done with it. Within a few years of WWII ending, most celebrations of the Hitler and Nazi regime were banished from public view. The statue of Sadam Hussein, ceremoniously toppled by the Iraqi people with the support of the American Army, was apparently scrapped. So what to do with Colston? Leave him at the bottom of the harbour?

I think it should be raised and be the first element in a sculpture park of fallen statues - like the memorial parks to the tyranny statues in the former Soviet Union. I visited the Moscow park years ago, before it was “improved” and there was an eerie power to the old monsters ten times larger than life lying on their backs and looking blankly at the sky, flowers trailing over their sleeping chests. Bristol could lead the way in this - turning a statue to honour a slaver into a memorial for those who have suffered slavery. Turning a proud boast into a supine symbol. Slavery was a crime against humanity, no slaver's statue should be in any place of honour.

Image: Felix Farley’s Bristol Journal 2nd August 1760. The advert reads: To be Sold, A Negroe Boy, about ten Years old, He has had the Small-Pox.