28th March 2013

A foreword by Philippa Gregory

Anya Seton was one of the leading writers – mostly women – who dominated the discipline of historical fiction after the second world war, and whose critical and popular acclaim continued until the late 1950s when fashions in literature changed.

The popularity of the post-war realist novel – grimy, gritty, and contemporary, and the enthusiasm for experimental novels, meant that traditional works by such writers as Seton, Georgette Heyer, and Jean Plaidy, maintained some of their readers; but lost the approval of the critics. Quite wrongly, critics came to regard historical fiction and romantic fiction as one and the same genre; and condemned both for being fantastical, escapist vehicles for predictable love stories suitable only for women readers who required entertainment but no intellectual challenge.

But a good historical novel has characters whose basic humanity engages our empathy and whose convincing circumstances remind us that the past is, indeed, another country. This is the opposite of romance fiction which is drawn to historical settings: not because it aims to explore how people are affected by the society in which they live; but because it depends on the imaginary glamour of the past: the long frocks and big hats, horse drawn transport, and high jeopardy. Romance fiction has no interest in different times and cultures, in the worst examples, its stories are told in a vacuum.

All but the very best romance fiction tends to deploy a limited number of character types: the heroine: vulnerable, pure, loving, the female villain: manipulative, sexual, heartless, the male villain: aggressive, uncontrolled, cruel, and the hero: loving, but often mistaken. The cardboard characters come ready-made, they are not forged by their particular experiences, by their history or by their society; nothing interrupts them working their way through their story to the happy ending.

High quality historical fiction is not like this. A good historical novel tells of characters who are entirely congruent with the known conditions of their time, and yet sufficiently independent in thought and action to stand out from the crowd, and for the modern reader to identify with them. They are rounded characters because they exist in a recognisable time and place and these circumstances work on them. A good historical novel is always conscious of the shared humanity that we all inherit: and – contradictorily – the way these deep instincts are moulded, repressed or even denied by the society in which we happen to be born.

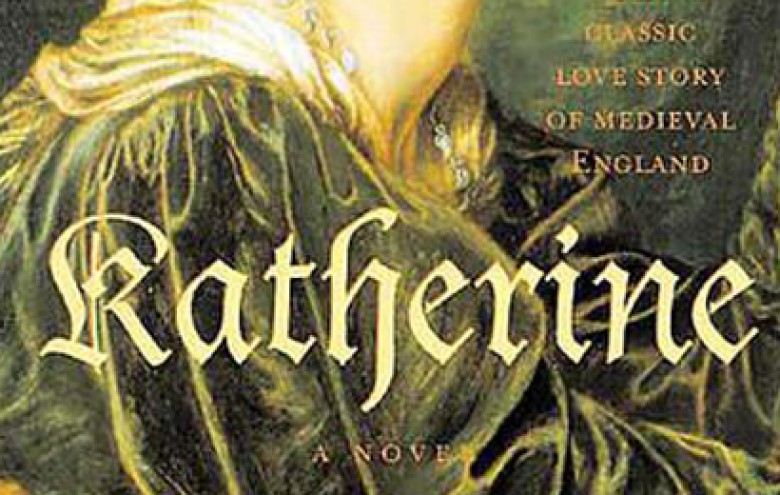

Such a novel is Anya Seton’s Katherine, often regarded as her finest book. It is set in the distant past of the (14th England, and Seton’s love of England and the English countryside is a powerful ingredient in this deeply felt book. It tells the story of Katherine – a convent-bred girl, who develops an inner strength in her arranged marriage to a boorish country squire, and who finds a deep and passionate love in her relationship with John, Duke of Lancaster, better known as John of Gaunt. The characters are vividly imagined and described, the detail of mediaeval England from the dirty streets to the excitement of feast days to the glamour of the royal palaces is splendidly evoked. Seton has an absolute command of her picture of England in the middle of the (14th and she describes it with confident flair.

First published in 1954 it is both a well-researched novel and very much a book of its time. Katherine’s sexual awakening and relationship with Duke John is concurrent with the historical facts, but is aligned with the morality of the 1950s in the way that she responds but does not initiate lovemaking, and is troubled by a very individualist post-1800 conscience. The faith in Freudian psychological explanations is pervasive: Duke John is first attracted to Katherine because of her resemblance to his first nurse, and his political decisions affected by his early fear of being a changeling.

Very many writers working today will acknowledge their debt to Seton and her peers, and the standards and style of that golden age of historical writing remains clearly influential. Personally, I devoured her work along with that of Georgette Heyer and from those two I undoubtedly formed my ideas of how a good historical fiction should be shaped. Both authors were absolutely committed to historical research as the backbone of the book, Seton uses her material very lightly, but Heyer’s work on the battle of Waterloo in The Infamous Army was so accurate that it is on the reading list for the British Army officer training. Neither Seton nor Heyer ever sacrifice historical accuracy for a good story – the history has to come first. Both of them use the technique of finding in the historical record and then re-creating as a fiction, a vibrant, fascinating character to lead the reader into this imaginary but powerfully researched world.

To read Seton is escapist – but not in the derogatory sense of the word. To read Seton is to enter into another time with such conviction that it seems as real as the present. It is not an easy or pretty time that she invites the reader to experience: it is dirty, cold, and dangerous; and life is often brutish and cut short. For women in particular, living in a society dominated by the power of men, survival is itself is a triumph, surviving with a sense of self intact – as Katherine superbly does – is a great adventure, powerfully told.

It is this feature that makes the novel such a powerful one for modern women. One cannot read the novel without gaining a sense that to be a woman, in any society, is a struggle between the desire to express oneself, and the compelling requirement to conform. In Katherine’s experience the demands of the society were to put her in an isolated and deserted manor house, where she was quite incapable of protecting herself from the many hazards. For women today the difficulties they face may be less a matter of life and death, but are nonetheless painfully and acutely felt. In the heroine Katherine we have an inspirational picture of a woman who deploys her courage and her sense of self worth. It’s an old novel, about an older time, but that message is as relevant today as it has ever been.