13th August 2015

Here’s two kisses: one between husband Petruchio and wife Kate. He has bullied the former shrew into submission and when he sends for her in a trial of authority she offers to put her hand beneath his boot to symbolize her duty.

Why, there's a wench! Come on, and kiss me, Kate.[i]

Here’s another kiss: Henry VIII has just threatened his sixth wife with a charge of heresy, which carries the death penalty. She hurries to his private room and denies that she has ever had a thought in her head: all men are superior to women.

(my modernization of spelling)And is it even so sweet heart, quoth the king? … and as he sat in his chair, embracing her in his arms and kissing her[ii]

The queen is Katherine Parr, the king called her Kate.

Is this the same kiss? Is there an extraordinary connection between the little-known queen and Shakespeare’s ‘problem’ comedy – The Taming of the Shrew? We know that Shakespeare studied the history of Henry VIII’s wives – did he use the bullying of Katherine Parr as a template for the bullying of Kate?

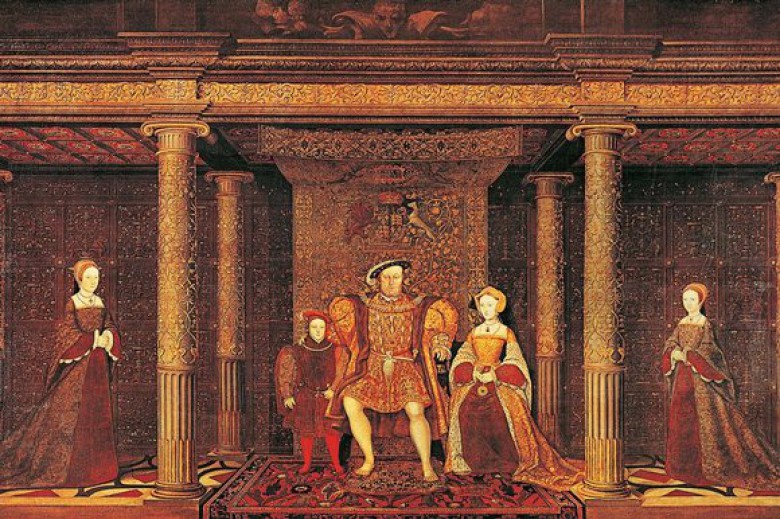

In 1544 the ageing indomitable Henry VIII had one last fling at France, leading a glamorous parade of nobility and an army of altogether 42,000 to set siege to Boulogne[iii] in his campaign to retake English lands in France. He left behind his new wife, Katherine Parr, demonstrating his trust in her by putting the running of his country in her capable hands. He made her Regent of England, the only wife to be so honoured since Katherine of Aragon 31 years and five wives earlier.

Kateryn (the name she called herself, signing her letters Kateryn the Quene KP) was to rule with a council of advisors. It was a big step for the new queen. She had been married to Henry for less than a year and had already demonstrated her skills as a royal wife – she was the first to bring together his unhappy and dispersed children: Lady Mary, the daughter of Katherine of Aragon denied her title, Lady Elizabeth, the declared bastard child of Anne Boleyn, and Prince Edward, the only surviving legitimate Tudor son and heir. Kateryn brought them to court for family occasions and when Henry was away she chose to have them to live with her for the whole of the summer.

She was experienced in running a castle and lands, she had even defended Snape Castle, Yorkshire, in a siege from rebels; and she understood the complexity of court life: her sister had been lady-in-waiting to all five previous royal wives. She was a scholar, teaching herself Latin, and studying the reform of religion. We can see – from her thoughtful directives to the country for racial tolerance and calm during wartime – that she enjoyed the exercise of just power. She was supremely tactful, reporting everything in detail to Henry and confirming all her decisions with him.

But she was also a woman who enjoyed herself. She loved beautiful clothes, especially shoes (in her first year as queen she bought 117 pairs!)[iv] and she loved music, dancing, sport and drama. She hired Nicholas Udall the playwright, and in the summer of 1544, while Henry was away, Udall wrote and staged a knockabout comedy for the queen’s summer court. It was called Ralph Roister Doister – a jolly piece with slapstick humour and jokes. It told of a household of women headed by a bold and confident woman, who fought off (sometimes with wit, sometimes physically) the approaches of a fortune-hunter and kept herself safe for the return of her true love from the war. The compliment to Kateryn, as the head of a kingdom waiting for the return of her husband, was obvious and friendly and – even more interestingly – Udall’s play for a ruling queen completely reversed one of the dominant themes of medieval story-telling and plays – the disciplining, abuse, and torture of wives.

In many medieval dramas a wife was portrayed as either a good wife, tested beyond endurance by an abusive husband, or a shrew, brought to obedience by a savage teacher. In the ‘patient Griselda’ stories, a woman is tortured by her paranoid husband who tests her wifely deference with a series of agonizing tests. His last and final hurdle, having taken her children from her and told her they are dead, is to bring their daughter home and announce that she will be his new wife and he will put patient Griselda to one side. Griselda agrees that the new arrival is more beautiful than herself; she asks only that he does not torment this new wife as he has done her, as she may be less able to bear it. The husband, finally seeing that Griselda is a wife of outstanding submissiveness, rewards her with his love, introduces her to her own children who have been hidden from her for years, and that is what passes as a happy ending for this archetypal story.

‘Shrew stories’ are the patient Griselda trials offered with more justification. A shrew-wife is usually one from the upper classes who will not lower herself to labour for her lower-class husband. Out of respect for her status he cannot bring himself to discipline her as he should. So instead of simply beating her he invents novel ways to reduce her pride. A tanner wraps his wife in a dead horse-skin, one man overthrows the table and starves his wife at every mealtime, one takes his wife on unbearably long journeys. In the end the wife succumbs and takes up her wifely duties – the shrew is tamed.

In Ralph Roister Doister the person who will not fit into his social place is the man, Ralph himself. It is he who is tamed by the spirited defence of the women who reject his advances, refuse to let him eat with them, and bundle him away. The comedy centres on his chivalric pretensions and the women’s robust rejection. He aspires to his lady and threatens to die for love, but he is never in any real danger – unlike the abused wives in the traditional stories.

We don’t know if Kateryn enjoyed this play about women’s control of their own lives, we don’t even have a certain record of its performance before her. But we do have evidence of the play’s extraordinary afterlife when William Shakespeare took it, with other ‘shrew’ plays, as part of his inspiration for The Taming of the Shrew, revised, and perhaps even added potent elements of the real-life story of Kateryn the Quene herself.

In later years Kateryn herself was ‘tamed’ and that by a king whose record in abusing and destroying women was unmatched. Kateryn’s studies had led her to become the leader of the reform party at court. Archbishop Thomas Cranmer in the church, and she at court, led the way in questioning the theology of the Roman Catholic Church, claiming that the primacy of the pope and ritual practices of the church had been corrupted. The reformers called for a return to the Bible in the movement that would become Protestantism.

Kateryn worked with Thomas Cranmer in translating the Latin of the Mass into English. She translated psalms and prayers, even composing her own, and publishing them with the king’s permission under her own name, becoming one of the first women writers to publish in English. Anne Askew – the famous reformer gospeller – probably preached in Kateryn Parr’s rooms, and her persecution and martyrdom was probably part of an attack by the traditionalists against the reforming queen. By 1545, in her second year of marriage, with the king back from France with only Boulogne to show for his efforts, with his health in decline, the king turned against his younger wife and her beliefs and started to listen to the counter-reformation party and incline back towards the Church of Rome. He no longer relished a clever, vocal, challenging young wife, he complained that she was not suitable for him.

William Shakespeare would have read what happened to the queen in Foxe’s Book of Martyrs (1563):

(my modernization of spelling) For the king at that time showed himself no less prompt and ready to receive any information, than the Bishop was maliciously bent to stir up the king’s indignation against her. The king immediately upon her departure from him, used these or like words: A good hearing (quoth he) it is when women become such Clerks, & a thing much to my comfort, to come in mine old days to be taught by my wife.

The Bishop hearing this, seemed to dislike that the Queen should so much forget herself, as to take upon her to stand in any argument with his majesty, … and said that it was an unseemly thing for any of his Majesty’s subjects to reason and argue with him, so malapert, and grievous … inferring moreover how dangerous and perilous a matter it is and ever hath been for a Prince, to suffer such insolent words at his subjects hands: who as they take boldness to contrary their sovereign in words, so want they no will but only power and strength to overthrow them in deeds.

Besides this, that the Religion by the Queen so stiffly maintained, did not only disallow and dissolve the policy & politic government of Princes, but also taught the people that all things ought to be in common, so that what colour so ever they pretended, their opinions were in deed so odious, and for the Princes estate so perilous, that (saying the reverence they bare unto her for his Majesties sake) they durst be bold to affirm that the greatest subject in this land, speaking those words that she did speak, and defending those arguments that she did defend, had with indifferent justice, by law deserved death.[v]

And Shakespeare – reading this perhaps in his childhood, for every cathedral and many homes had copies of the ‘Book of Martyrs’ – may have noted how a queen named Kate was tamed by her husband by being frightened into obedience.

Hunger, arduous travel and domestic discomfort were deployed to humble the Kate of The Taming of the Shrew. Her husband Petruchio refuses to believe that things are good enough for Kate. In a pun on the old word for household goods: ‘cates’,[vi] he shows his wife that he is an insanely extravagant demanding consumer, nothing is good enough for Petruchio; just as no woman can satisfy the king who judicially killed two wives, and abandoned two others. The legendary feasts of Henry VIII and the extravagance of his court created a storm of consumption that whirled around the Tudor throne, Henry as demanding as Petruchio, Kateryn the Quene at the centre like Kate – everything is for her and yet she owns nothing.

All the ‘shrew’ plays, Shakespeare’s among them, are a study in how a woman’s mind can be brought to obedience. Petruchio does it by simply denying reality until she is too exhausted to maintain her own belief.

PETRUCHIO

Come on, i' God's name, once more toward our father's.

Good Lord, how bright and goodly shines the moon!

KATHERINE

The moon? The sun! It is not moonlight now.

PETRUCHIO

I say it is the moon that shines so bright.

KATHERINE

I know it is the sun that shines so bright.

PETRUCHIO

Now, by my mother's son, and that's myself,

It shall be moon, or star, or what I list,

Or e’er I journey to your father's house.

Go on, and fetch our horses back again.—

Evermore crossed and crossed, nothing but crossed!

HORTENSIO

Say as he says, or we shall never go.

KATHERINE

Forward, I pray, since we have come so far,

And be it moon, or sun, or what you please.

And if you please to call it a rush candle,

Henceforth I vow it shall be so for me.

PETRUCHIOI say it is the moon.

KATHERINEI know it is the moon.

PETRUCHIO

Nay, then you lie. It is the blessèd sun.

KATHERINE

Then God be blest, it is the blessèd sun.

But sun it is not, when you say it is not,

And the moon changes even as your mind.

What you will have it named, even that it is,

And so it shall be so for Katherine.

HORTENSIO

Petruchio, go thy ways, the field is won.[vii]

Modern victims of domestic abuse have a name for the process of denying observed reality. They call it ‘gaslighting’ after the play by Patrick Hamilton in which a husband makes his wife think that she is delusional by dimming the illumination in their home. In Taming of the Shrew Kate surrenders her observation and knowledge, in the taming of Kateryn Parr she too gives up any claim to independent thought.

John Foxe describes her bowing to superior male spirituality and acknowledging natural womanly weakness and inferiority. Kateryn calls herself a ‘silly poor woman’ whose judgement must be determined by her husband.

(my modernization of spelling) Your Majesty (quoth she) doth right well know, neither I my self am ignorant, what great imperfection & weakness by our first creation, is allotted unto us women, to be ordained and appointed as inferior and subject unto man as our head, from which head all our direction ought to proceed: and that, as God made man to his own shape and likeness, whereby he being endued with more special gifts of perfection, might rather be stirred to the contemplation of heavenly things and to the earnest endeavour to obey his commandments: even so also made he woman of man, of whom and by whom she is to be governed, commanded and directed. Whose womanly weakness and natural imperfection, ought to be tolerated, aided and borne withal, so that by his wisdom such things as be lacking in her, ought to be supplied.

Since therefore that God hath appointed such a natural difference between man and woman, and your Majesty being so excellent in gifts and ornaments of wisdom, and I a silly poor woman so much inferior in all respects of nature unto you: how then cometh it now to pass that your Majesty in such diffuse causes of Religion, will seem to require my judgment? Which when I have uttered and said what I can, yet must I and will I refer my judgment in this and all other cases to your Majesty's wisdom, as my only anchor, supreme head, and governor here in earth next under God, to lean unto.[viii]

Shakespeare shows Petruchio’s victory over Kate. She gives a speech about obedience, she offers to put her hand under his foot and he exclaims:

‘Why, there’s a wench! Come on, and kiss me, Kate.’[ix] and kisses her in public. The kiss – and how potent is a kiss in Christian iconography, and how rarely it denotes affection! – is not a kiss of sexual attraction, they are in public at a feast at her father’s house. The kiss is to demonstrate his complete ownership of her: she does not control her lips, or her body, her husband can take it or leave it as he pleases. She offers to put her hand under his foot, he chooses to demand a kiss. He is her authority, her discipline, she puts her lips to his as a medieval supplicant would kiss the ring of the pope, or as a medieval child might kiss the rod that was going to beat her, to acknowledge the authority.

Kateryn Parr, surrendering her intellectual independence to the king, declaring that she knows nothing but what her husband teaches her, is pulled onto his lap before the court and commanded to kiss him.

(my modernization of spelling)And is it even so sweet heart, quoth the king? And tended your arguments to no worse an end? Then perfect friends we are now again, as ever at any time heretofore: and as he sat in his chair, embracing her in his arms and kissing her, he added this saying: that it did him more good at that time to hear those words of her own mouth, than if he had heard present news of a hundred thousand pounds in money fallen unto him.[x]

This is perhaps one of the most interesting kisses ever. It crosses from reality – if, indeed, it happened at all – into Foxe’s history of martyrdom, perhaps into Shakespeare’s comedy of abuse, and from there into the title of a Hollywood musical ‘Kiss me Kate’ (1953). It is, as Shakespeare states in Richard III, a better alternative to speech for women:

Teach not thy lip such scorn, for it was made

For kissing, lady, not for such contempt.[xi]

If Kateryn Parr was indeed the inspiration for Shakespeare’s Kate, it’s interesting to see how history has done for her what the king wanted to do, what Shakespeare did – take the opinion from the woman and deny her scholarship. Nineteenth-century historians tell us that Kateryn was Henry’s last queen, the nurse to his old age, the one who survived the invalid of sinking powers. Closer research shows a woman who studied without the king’s permission, who drew her own conclusions, who wrote and published thoughts that he would name as criminal heresy, and who survived by denying her scholarship and herself. Shakespeare with Kate and history with Kateryn have reduced an independent woman to a handmaiden. It’s time that we looked at their stories again.

[i] William Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew, Folger Shakespeare Library, Act 5, Scene 2, Page 221. http://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/PDF/Shr.pdf

[ii] John Foxe, Acts and Monuments, 1570 Edition, Book 8, Page 1464. http://www.johnfoxe.org/index.php?realm=text&goto...

[iii] 42,000. https://books.google.ie/books?id=gT8qlUPkRJEC&pg=P...

[iv] Linda Porter, Katherine the Queen: The Remarkable Life of Katherine Parr, Pan Macmillan.

[v] John Foxe, Acts and Monuments, 1570 Edition, Book 8, Page 1462.

[vi] Household Kates: Domesticating Commodities in The Taming of the Shrew Author(s): Natasha Korda Source: Shakespeare Quarterly, Vol. 47, No. 2 (Summer, 1996), pp. 109-131 Published by: Folger Shakespeare Library in association with George Washington University Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2871098

[vii] William Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew, Folger Shakespeare Library, Act 4, Scene 5, Pages 185–187.

[viii] John Foxe, Acts and Monuments, 1570 Edition, Book 8, Page 1463.

[ix] William Shakespeare, The Taming of the Shrew, Folger Shakespeare Library, Act 5, Scene 2, Page 221.

[x] John Foxe, Acts and Monuments, 1570 Edition, Book 8, Page 1464.

[xi] William Shakespeare, Richard III, Folger Shakespeare Library, Act 1, Scene 2, Pages 33–35. http://www.folgerdigitaltexts.org/PDF/R3.pdf