Margaret Beaufort, a descendant and passionately loyal supporter of the House of Lancaster, was married, while still a child of twelve, to the king’s half-brother Edmund Tudor, as a way of endowing him with her enormous fortune and lands.

Her husband died of plague leaving her a thirteen-year-old widow with a baby son and she was speedily remarried by her family; but the triumph of York meant that the new king Edward ordered her little boy Henry Tudor into the guardianship of one his favourites. Margaret must have thought that she would never live with her son, or see her true king, again. All she could do was to hope that the House of York would destroy itself.

It looked as if she was right to hope. The York court was riven with faction, and in 1470 their advisor and mentor, Richard Neville Earl of Warwick, turned against them and restored King Henry of Lancaster to the throne.

This was a great moment for Margaret Beaufort. Acknowledged as a great heiress of the House of Lancaster she summoned her son Henry Tudor and took him to be presented to his half-uncle, the King of England. She would weave a legend around this meeting, saying that the king had greeted his half-nephew saying that the boy would be greater than any of them.

The Lancastrian triumph did not last for long. Edward the exiled York king recaptured the throne, killing the Lancaster heir in battle and possibly ordering the murder of the king. Henry Tudor had to flee into exile with his uncle Jasper and Margaret was widowed for the second time and alone.

With brilliant political skills, Margaret selected the most powerful and trusted supporter of York to be her husband number three. She wanted a man who was clever enough to see that her son might have a chance at the throne one day, and duplicitous enough to serve two sides at once.

She found a perfect partner in Thomas Lord Stanley. They married, and he introduced Margaret to her enemy’s court where she became so well liked that Elizabeth chose her as a godmother for one of the princesses.

But then, unexpectedly, Edward the king died and the throne was seized by his brother Richard of Gloucester. Margaret, smoothly, befriended the new queen Anne, and was first lady of her court, carrying Anne’s train at the glamorous coronation.

As Richard and Anne celebrated their accession to the throne, their apparently dear friend Margaret Beaufort played a double game, weaving the dissatisfied Duke of Buckingham into an alliance with her and with the former queen, Elizabeth. She betrothed her son Henry Tudor to Elizabeth’s daughter, Princess Elizabeth, and when the Duke of Buckingham raised his men for a rebellion against Richard III he was counting on the arrival of Henry Tudor and his troops. They never came. Bad weather kept them in port, and the Beaufort rebellion was washed out in a deluge of rain. The two Princes in the Tower had disappeared, and were said to be dead.

Whether Margaret had a hand in their disappearance or not, we still cannot know. She certainly had a motive: if the York boys were dead then her son would be the next heir, from the Lancaster side of the family. Placed in London with a superb spy network and men loyal to her, she was probably able to do so. And it is significant that though she and her son blackened the reputation of Richard III, they never actually accused him of murdering the boys.

King Richard knew Margaret had been plotting against him but he trusted her husband to keep her under house arrest. She never stopped plotting for her son, and when he finally invaded and rode onto Bosworth Field it was Margaret who provided the ally, the husband she had married for this very moment.

Henry Tudor won the battle saved by his stepfather’s cavalry; he received his crown on the battlefield from his step-uncle’s hands. His first act after marching into London was to retreat with her for two long weeks, to celebrate their triumph and to plan their future.

She was a co-ruler of England, housed in every royal palace in the best rooms often with interconnecting doors to her son. She wrote the Book of the Royal Household, determining how state and private occasions should be performed. She was a keen landlord of her vast lands, and took an active part in the government of the kingdom. She outlived her adored son and survived long enough to see her grandson Henry inherit the throne.

Perhaps best of all she invented her own title – she called herself ‘My Lady, the King’s Mother’ and she signed her name like a royal: Margaret R – Margaret Regina.

Margaret Beaufort is of the House of Lancaster, Edmund Tudor is the son of a queen of England. Any child they conceive will have an impressive lineage, English royal blood on one side, French royal blood on the other, both of them kin to the King of England.

‘Is the king making his brother over-mighty?’ the queen whispers.

‘Oh, look at her,’ I say gently. ‘She is a tiny little thing, and a long way from marriageable age. Her mother will keep her home for another ten years, surely. You will have half a dozen babies in the cradle before Edmund Tudor can wed or bed her.’

We both look down the room at the girl whose little head is still bobbing up and down as if she wishes someone would speak to her. The queen laughs. ‘Well, I hope so, surely a little shrimp like that will never make a royal heir.’

From The Red Queen

He looks up from his seat at the table, his quill poised over the silver inkpot. ‘You told me when we married that you were given to God and to your cause,’ he reminds me. ‘I told you I was given to the furtherance of myself and my family. You told me that you wished to live a celibate life, and I accepted this in a wife who brought a fortune, a great name, and a son who has a claim to the throne of England. There is no need for affection here, we have a shared interest. You are more faithful to me for the sake of our cause, than you would ever be for any affection, I know that. If you were a woman who could be ruled by affection you would have gone to Jasper and your son a dozen years ago. Affection is not important to you, nor to me. You want power, Margaret, power and wealth; and so do I. Nothing matters as much as this to either of us, and we will sacrifice anything for it.’

‘I am guided by God!’ I protest.

‘Yes, because you think God wants your son to be King of England. I don’t think your God has ever advised you otherwise. You hear only what you want. He only ever commands your preferences.’

I sway as if he has hit me. ‘How dare you! I have lived my life in His service!’

‘He always tells you to strive for power and wealth. Are you quite sure it is not your own voice that you hear, speaking through the earthquake, wind and fire?’

I bare my teeth at him. ‘I tell you that God will have my son Henry on the throne of England and those who laugh now at my visions and doubt my vocation will call me “My Lady, the King’s Mother”, and I shall sign myself Margaret Regina, Margaret R ...’

From The White Queen

I take the note to the window for the light, and as the river gurgles beneath the window I read it. It is sealed with the crest of the Beauforts. It is from Margaret Stanley, my former lady-in-waiting. Despite being Lancaster born and bred, and mother to their heir, she and her husband Thomas Stanley have been loyal to us for the last eleven years. Perhaps she will stay loyal. Perhaps she will even take my side against Duke Richard. Her interests lie with me. She was counting on Edward to forgive her son his Lancaster blood and let him come home from his exile in Brittany. She spoke to me of a mother’s love for her boy and how she would give anything to have him home again. I promised her that it would happen. She has no reason to love Duke Richard. She might well think her chances of getting her boy home are better if she stays friends with me and supports my return to power.

When Edward was on the throne the boy was many steps from being an heir, yet even so Edward would have taken him to the Tower, would quietly have seen to his death. That is why Margaret Beaufort kept him far away, and negotiated very cautiously for his return. I even pitied her as she missed her son. She even sympathised with me when George was going to send his son away. I thought we had an understanding. I thought we were friends. But all the time she was waiting. Waiting and thinking when her son could return, an enemy to the King of England whether the king was Edward or my husband Richard.

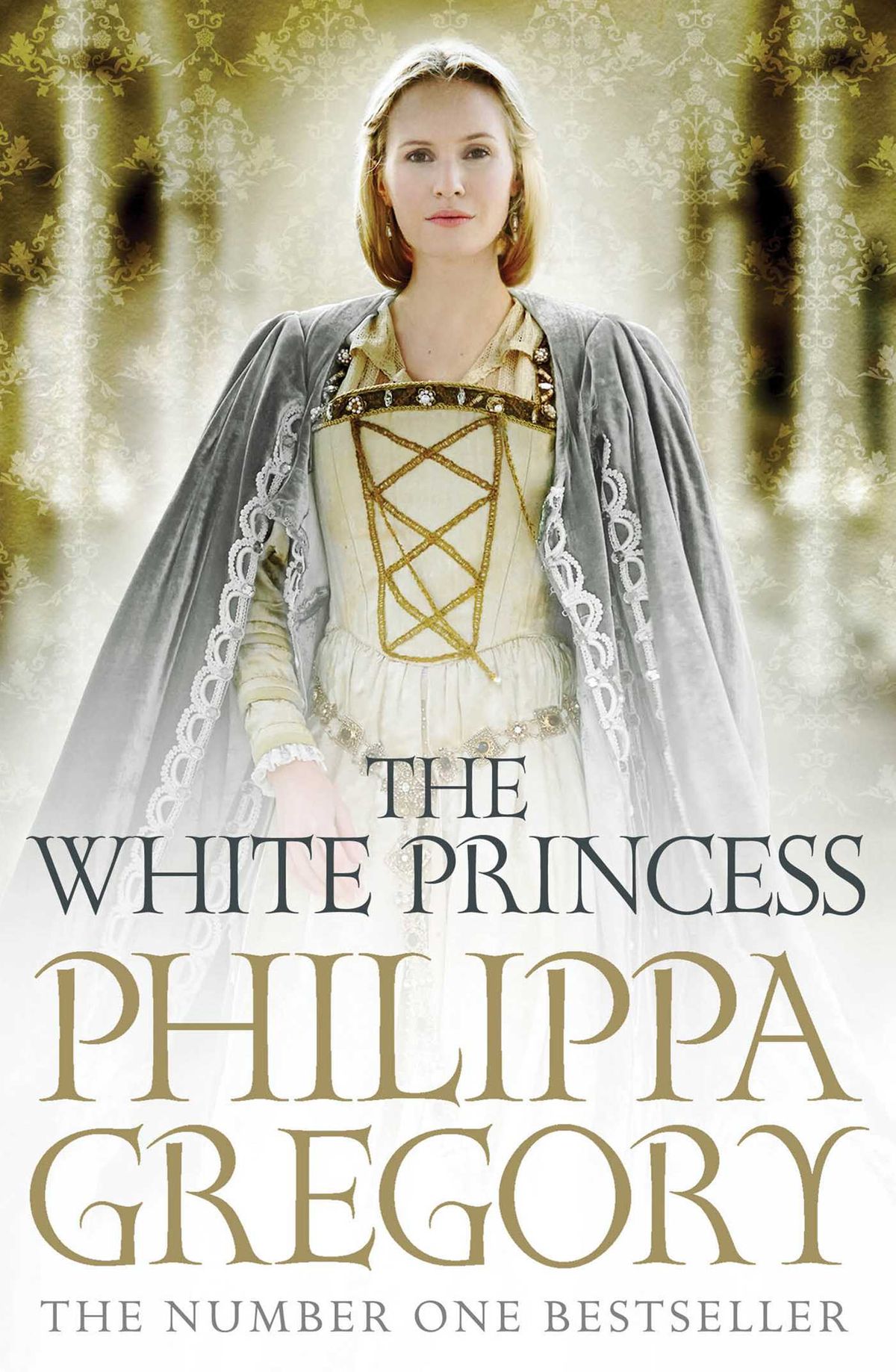

From The White Princess

A second barge carries My Lady the King’s Mother, seated in her triumph on a high chair, almost a throne, so that everyone can see Lady Margaret sailing into her own at last. Her husband stands beside her chair, one proprietorial hand on the gilded back, loyal to this king as he swore he was loyal to the previous one, and the one before that.

Beyond her, his flint-faced mother, Margaret Beaufort, watched the young couple with a glimmer of a smile. This was England’s triumph, this was her son’s triumph, but far more than that, this was her triumph – to have dragged this base-born bastard family back from disaster, to challenge the power of York, to defeat a reigning king, to capture the very throne of England against all the odds. This was her making. It was her plan to bring her son back from France at the right moment to claim his throne. They were her alliances who gave him the soldiers for the battle. It was her battle plan which left the usurper Richard to despair on the field at Bosworth, and it was her victory that she celebrated every day of her life. And this was the marriage that was the culmination of that long struggle. This bride would give her a great-grandson, a Spanish–Tudor king for England, and a son after him, and after him: and so lay down a dynasty of Tudors that would be never-ending.

From The King's Curse

I walk into the presence chamber of the King of England and see the prince, not on his throne, not standing in a stiff pose under the cloth of estate as if he were the portrait of majesty, but laughing with his friends strolling around the room, with Katherine at his side, as if they were a pair of lovers, enchanted with each other. And at the end of the room, seated on her chair with a circle of silent ladies all around her, a priest on either side for support, is My Lady, wearing deepest black, torn between grief and fury. She is no longer My Lady the King’s Mother – the title that gave her so much pride is buried with her son. Now, if she chooses it, she can be called My Lady the King’s Grandmother, and by the thunderous look on her face she does not choose it.

Image: Margaret Beaufort by unknown artist, National Portrait Gallery (NPG 551)